Lysine: A Deep Dive into Its Role, Origins, and Future

Historical Development

In 1889, the German chemist Ferdinand Heinrich Edmund Drechsel identified a new amino acid as he worked with casein, a protein found in milk. Named lysine, this discovery eventually found its way into the heart of nutrition and food science. The story of lysine tracks closely with the industrial revolution of food processing—early on, natural sources served best. Scientists dug deeper into fermentation and biological manufacturing and turned lysine into a product with remarkable reach. During the 20th century, commercial production scaled from extraction from protein hydrolysates to efficient microbial fermentation. By the 1960s, researchers in Japan figured out how to use Corynebacterium glutamicum, a bacterium that eats glucose from crops. This innovation triggered a quiet revolution in livestock nutrition, and supplementation transformed animal growth and protein yield. As the industry matured, manufacturers in Asia, Europe, and North America improved yields, cut costs, and honed product consistency, solidifying lysine’s place in modern nutrition.

Product Overview

Lysine stands out among essential amino acids, mainly because the human body cannot manufacture it. That means regular dietary intake becomes a necessity, whether for people or for the vast numbers of animals fed in agriculture. Major products come as crystalline white powders, granules, or liquid concentrates, with the most common commercial forms being L-lysine hydrochloride and L-lysine sulfate. These products travel globally, shipped in robust packaging for animal feed, nutrition bars, and medical formulations. Livestock operations, fish farms, and food companies depend on lysine’s reliable supply, often sourced through well-established distributors who monitor traceability and quality closely.

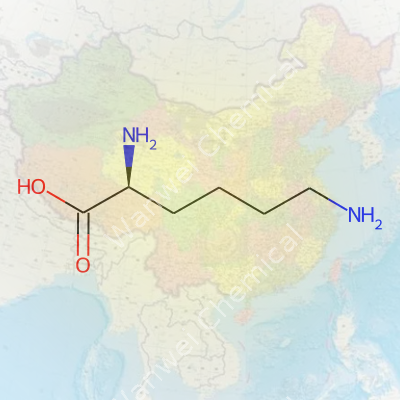

Physical & Chemical Properties

As a compound, lysine appears as a white, odorless powder, soluble in water, and hygroscopic. The molecular formula, C6H14N2O2, describes an α-amino acid with a straight chain and a terminal amino group. This extra amino group gives lysine a basic character in solution. Under regular conditions, the hydrochloride form stays stable but draws moisture from the air if not kept in tight containers. Pure lysine usually melts above 200°C, and the compound remains stable in dry, cool storage conditions. In acidic or neutral baths, lysine stands up to heat, but it might degrade under intense alkaline environments or extended heating, which means careful handling during feed and food processing.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Industry suppliers follow set specs, with L-lysine hydrochloride typically at 98.5% or higher purity. Heavy metals, moisture, and microbial contaminants stay far below legal limits, as per regulations set by bodies like the FDA, European Food Safety Authority, and China’s GB standards. Bulk sacks and drums carry standardized labels listing contents, origin, net weight, manufacturing batch, and relevant certifications. Feed labels must state the product’s amino acid composition, its net lysine content (usually calculated as L-lysine base), and the recommended amount for safe animal nutrition. Traceability marks and QR codes link to test reports, offering transparency to buyers. The aim is consistent quality backed by reliable documentation, helping nutritionists and feed millers dose animals correctly.

Preparation Method

Most lysine production takes place in fermentation tanks using genetically enhanced strains of Corynebacterium or related microbes. These bacteria thrive on glucose derived from corn, sugar cane, or other crops, converting carbohydrates into L-lysine through a carefully managed fermentation process. The broth is periodically sampled, and when lysine levels peak, operators stop fermentation and initiate purification. Filtration pulls out bacterial mass. Ion exchange columns separate lysine from other byproducts. Chemical precipitation or concentration produces purified lysine, which is then dried, milled, and cooled. Sometimes the base is converted into the hydrochloride or sulfate salt to stabilize and standardize the product before packing. Years of R&D fine-tuned strain genetics and culture conditions, squeezing ever more lysine from every kilogram of raw material.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

In metabolism, lysine participates in protein synthesis, linking up with other amino acids in peptide chains. Under laboratory settings, the amino and carboxyl groups allow various chemical modifications—acetylation, succinylation, methylation, and hydroxylation are just a few reactions. Scientists have used isotopically labeled lysine to track metabolic flux in cells. In food science, lysine reacts with reducing sugars during heating, causing Maillard browning. This reaction can degrade nutritional value, especially in heat-treated milk or bread, leading to potential shortages of accessible lysine in processed foods. Careful control of heat and moisture during feed and food manufacture helps prevent excessive lysine loss, and supplementers account for this in their quality controls.

Synonyms & Product Names

You’ll find lysine under different trademarks and technical names. The main substance appears as L-lysine, with salts like L-lysine hydrochloride and L-lysine sulfate. Some suppliers market it as feed-grade lysine or pharmaceutical-grade lysine for different applications. Chemists refer to it with a systematic name: (S)-2,6-diaminohexanoic acid. The E number for food additives is E640. The CAS number for L-lysine is 56-87-1. These identifiers make purchasing and regulatory review far simpler, connecting large buyers and regulators to exactly the right compound.

Safety & Operational Standards

Producers follow safety rules on a global scale. Occupational guidelines require dust control, proper ventilation, and the use of gloves and masks during handling to prevent irritation and respiratory exposure. Environmental regulators demand tight limits on wastewater discharge from fermentation units, pushing for green processes and minimal residual waste. On the animal nutrition side, authorities issue maximum permitted concentrations to ensure lysine use stays within healthy bounds for livestock. Blending plants maintain HACCP protocols, keeping contaminants away and logging every batch. Major certifiers, including GMP and FSSC 22000, routinely audit lysine plants. In medicine and dietary supplements, manufacturers comply with stricter guidelines for purity, allergens, and labeling, using pharmaceutical clean rooms and validated processes.

Application Area

Farmers and feed manufacturers treat lysine as a cornerstone nutrient—adding it to pig, poultry, and aquaculture diets to match precise amino acid profiles. Supplementing lysine in pig diets lets nutritionists cut back on expensive soybean meal while keeping growth on track, cutting both feed costs and environmental load from excess nitrogen. Chicken, fish, and pet foods get custom blends, often paired with methionine and threonine, to supply balanced, digestible protein. Beyond feed, the food industry uses lysine in sport nutrition and high-protein foods, helping fortify breakfast cereals, plant-based meats, and medical shakes. Medical researchers test lysine in wound healing creams, herpes virus treatments, and as a component of intravenous nutrition solutions. Even chemical manufacturers tap lysine as a feedstock for bioplastics and specialty chemicals, like caprolactam.

Research & Development

University labs and corporate R&D teams explore all angles of lysine innovation. Microbiologists hunt for next-generation bacterial strains with even higher yields or lower sugar inputs. Synthetic biology opens the door to customizing metabolic pathways, producing lysine from uncommon feedstocks or side-streams like glycerol. Nutritionists study how adjusting lysine ratios in animal feed alters meat quality, growth rates, and disease resistance, publishing thousands of field trials. In medicine, researchers look at lysine’s role in bone health, calcium absorption, viral inhibition, and its relationship with other nutrients like arginine. Chemists probe structure-activity relationships, discovering new lysine analogues with specialized biomedical functions. Real-world field data drives constant review, linking product quality to animal performance, food fortification, and clinical outcomes.

Toxicity Research

Lysine holds a solid track record for safety in both animals and humans. Extensive studies show very high tolerance levels in pigs, poultry, fish, dogs, and people, with the major risk being metabolic imbalance only if extreme overdose continues for weeks or months. Regulatory agencies set recommended daily allowances for humans, usually in the range of one to two grams per day for adults, and feed regulations in livestock recipes stay well beneath toxicity thresholds. Animal trials at concentrations far higher than practical feeding levels show mild gastrointestinal effects, typically in the form of transient diarrhea or changes to kidney function at extreme doses. No mutagenic or carcinogenic risks have appeared in credible studies. Regular reviews by the FAO, WHO, and EFSA confirm lysine’s safe status in commercial applications.

Future Prospects

Lysine research and manufacturing outlook stays busy on several fronts. Precision fermentation, driven by new genetic engineering tools, stands poised to lower production costs even further and tap non-traditional raw materials such as agricultural waste. This could ease pressure on global corn and sugar supply chains. Plant-based foods, alternative meats, and sustainable fish farming require extra lysine, especially as consumers push for lower environmental footprints and higher plant protein content. Human food manufacturers eye fortification strategies to counter amino acid deficits in staple foods, especially as populations age or shift towards vegan diets. Medical research inches forward, looking at lysine’s potential in viral disease prevention, kidney functions, and as a carrier for targeted nutrients or drugs. Traceability and carbon footprint labeling could become basic requirements, raising the bar for quality, transparency, and accountability. The story of lysine continues to evolve, tightly linked to technology, nutrition, and global food security.

What Lysine Really Does

Lysine plays a big role in health and nutrition, both for people and for animals. Every cell needs amino acids to function, and lysine counts as one of the essentials—meaning you can’t make it from scratch in your body. So, you need to get it from food or supplements.

Athletes, vegans, or anyone paying attention to what they eat might recognize lysine as a building block for muscle. That’s not just gym talk; lysine helps put together proteins that keep your muscles, skin, and bones in good shape. If you skip out on it—let’s say you eat lots of wheat and corn and not much dairy, eggs, meat, or beans—you could start to see the effects pretty quickly. Poor wound healing, feeling tired, maybe even hair loss. All those aches you feel when your muscles take days to recover, or broken skin that won’t mend? Lysine plays a part in patching those up.

People fighting frequent cold sores have heard of lysine, too. The herpes simplex virus, which causes those pesky blisters, needs another amino acid called arginine to multiply. Lysine seems to help keep arginine pinned down, slowing viral growth. That’s why pharmacy shelves have tubs of lysine ointment or capsules—regular daily doses can shorten outbreaks and space them farther apart.

Animal Feed and Food Production

Farmers have known about lysine’s importance for a long time. Most animal feed, especially for pigs and chickens, relies on grains that skimp on lysine. By boosting feed with lysine, livestock grow faster and healthier. This translates to more nutritious meat, and farmers use resources more efficiently. China and the US alone churn out hundreds of thousands of tons of synthetic lysine each year, mostly for feed. When prices surge, so do feed costs, meaning higher grocery bills for all of us.

Where You Find Lysine

Diets rich in dairy, eggs, fish, poultry, and lean meats usually cover lysine needs with no problem. Vegetarians who load up on legumes and beans get a decent supply, too. For others, especially folks relying on cereals as a staple—think big bowls of rice or wheat at every meal—the numbers drop. Adding soy products, lentils, or quinoa can help plug that gap. In food science, some companies add lysine straight to flour or milk powder in poorer regions, trying to head off malnutrition before it begins.

Bigger Picture and Ideas for the Future

Lysine doesn’t just matter at the individual level; it links to big-picture issues like food security, sustainability, and public health. With the world’s population on track to hit nearly 10 billion by 2050, every tool that makes food production more efficient helps. Using lysine wisely in crops or animal feeds stretches things further, offering more nutrients for less input and less waste.

Researchers have even looked into bioengineering plants to boost their natural lysine content. Some corn varieties now pack more lysine, reducing the need for extra supplements and making meals more nutritious for everyone, especially in low-income countries.

The story of lysine stretches across the dinner plate, the medicine cabinet, and the farm. Paying attention to a single amino acid like this uses what we know about science, diet, and even economics to tackle bigger challenges, making sure that growth and health go hand in hand for more people.

Why People Reach for Lysine

Many folks turn to lysine to support their immune systems or to keep pesky cold sores in check. Lysine is an amino acid, something our bodies use to build protein. It comes in food like meat, fish, and dairy, but supplement companies bottle it as a potential fix for cold sore outbreaks and, sometimes, for muscle recovery or anxiety.

Examining Side Effects: Not Always What You Hear

The supplement aisle offers plenty of promises, and people often assume anything available without a prescription must be harmless. Lysine is usually safe for short-term use when taken in reasonable doses. But real people have reported some side effects. Digestive troubles come up most often—nausea, stomach pain, and diarrhea. I remember starting a lysine regimen years ago for stress-related canker sores. Within a few days, my stomach started feeling like I’d eaten a brick. Cutting lysine cleared up the discomfort.

People with kidney or liver issues face higher risks. The kidneys handle amino acid processing, so flooding the system with too much lysine could lead to a backlog. Steve, a friend from my college days, took a heavy hand with protein shakes and amino acid pills while preparing for a powerlifting meet. His doctor spotted high kidney numbers on a routine blood test, which sent him scrambling to cut out supplements, including lysine. Routine overuse left his kidneys struggling with the overload.

Medical Guidance Should Come First

Labels on supplements rarely mention these potential side effects. The FDA treats supplements differently than prescription drugs, so makers don't have to run clinical trials of the same scale before putting products on shelves. The National Institutes of Health confirms lysine’s safety record for most healthy adults, but also points out that long-term safety hasn’t been studied as carefully as you’d expect for a product millions buy.

Supporting Claims with Facts

One 2015 review published in the journal Pharmacological Research evaluated lysine’s effect on herpes simplex virus. The evidence showed some promise for cold sore prevention, but side effects like stomach cramps popped up in about 3% of cases. A separate study in Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine found that combining lysine with arginine can disrupt the body’s electrolyte balance, which could cause heart rhythm issues for those with underlying health problems.

Solutions and Smarter Choices

Knowledge makes all the difference. Doctors can help match supplements to a person’s real needs and check for interactions. For those without enough lysine in their diets, food sources offer a safe route. Tough cases—long-standing cold sores or athletes pushing their limits—may want to consider a short trial of lysine, but always with medical supervision.

Supplements should not replace a good diet or proper medical care. The marketing around lysine and other amino acids can make it seem like there’s no downside, but stomach aches, kidney stress, and electrolyte troubles do happen. Open conversations with healthcare providers, honest self-assessment, and respect for your own limits remain the best tools to avoid trouble. Common sense, not chemistry, leads to better results.

Understanding Lysine’s Role in the Body

Lysine stands out as an essential amino acid. The human body cannot produce it on its own, so it has to come from food or supplements. This one supports muscle growth, helps rebuild tissue, and keeps the immune system in a healthy groove. Many people talk about it for reasons like managing cold sores or upping their athletic performance. In reality, balanced nutrition already handles this for most.

The Numbers: Recommended Daily Intake

Nutrition experts, backed by the National Institutes of Health and World Health Organization, set the daily requirement for lysine at about 30 mg per kilogram of body weight. For an average adult, that ranges between 2 to 3 grams a day. If you eat a diet with enough proteins—meat, eggs, dairy, fish, beans, or lentils—you probably hit this mark without extra effort.

Here’s where questions start. A person might read about lysine in fitness forums or health articles and think, “Should I take more?” Going higher sometimes happens for people managing cold sores. Some studies show that doses around 1 to 3 grams may shorten the duration or frequency of outbreaks. No good comes from assuming “more is always better,” though. Too much often stresses the kidneys, and doses above 6 grams for weeks at a stretch carry certain risks.

Facts From Reliable Research

Clinical trials suggest short-term lysine supplementation looks safe for most adults. Side effects stay rare, usually mild digestive troubles like cramps or nausea. Long-term safety data won’t fill pages. For people with kidney or liver conditions, extra caution becomes non-negotiable. For pregnant or breastfeeding women, best practice says stick with food sources and talk things over with a healthcare professional before reaching for a bottle of supplements.

Choose Food Over Supplements

My typical breakfast—Greek yogurt, a couple of eggs—already hits the daily lysine goal. For plant-based eaters, lentils, quinoa, and soy products work well. Meat, dairy, and fish all rank as packed sources. Relying mainly on supplements rarely fits the need unless a doctor sees evidence of a shortage, which remains rare outside of poorly nourished populations or special medical conditions.

Tight budgets sometimes push people to skimp on animal protein. Pulses and legumes deserve more credit—they supply lysine for folks skipping dairy or meat. Beans and lentils make their way into my own meals regularly; they’re a backbone of affordable nutrition.

Finding a Sensible Approach

If you suspect a lysine deficiency, look for signs like persistent fatigue, poor concentration, or regular viral outbreaks. Instead of self-diagnosing, chat with a doctor. Blood tests and a quick check-up define the real issue.

For most, aiming for two to three grams daily happens automatically, just by filling up a plate with a variety of whole foods. If you think you need a higher amount, stick to doses studied in research—no more than three grams a day—and bring a medical professional into the conversation, especially for regular use.

Better Decisions Based on Evidence

Healthy living leans on habits—sound eating, regular sleep, exercise—rather than loading up on single nutrients. Lysine earns its place in the balance, not as a miracle fix. Accurate information, sensible portions, and some self-awareness offer the best path toward real health.

Understanding Cold Sores

Cold sores, those painful blisters that show up near the mouth, often bring a sense of dread. Most folks know them as a sign that the herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) has flared up again. Stress, sunlight, and even changes in hormone levels can wake up this virus from its slumber. Once someone catches HSV-1, the virus tends to settle in for the long haul.

Lysine: A Simple Amino Acid With Big Hopes

Lysine landed in popular conversation because it’s an amino acid our bodies use to build protein. Some early animal studies in the 1970s saw that HSV-1 seemed less active in environments with more lysine present. A few small clinical studies followed, aiming to explore if lysine supplements could help prevent or speed up healing of these frustrating sores.

In practice, people often reach for lysine as a supplement and even swear it takes the edge off their outbreaks. I’ve talked to friends and patients who keep lysine tablets tucked away, ready at the first tingle. Online forums overflow with stories about reducing outbreak frequency and wound healing time, even if everyone’s bathroom cabinet stash looks a bit different.

Sorting Science From Stories

Research never claims a miracle cure. Some controlled trials have noted moderate benefits in prevention—especially at doses of around 1,000 mg to 3,000 mg per day. One Australian study in the 1980s reported that people who took lysine experienced fewer outbreaks. Still, bigger reviews often describe results as inconsistent. Not every person seems to notice a difference, which reminds us that bodies react in their own ways.

There’s also the question of the lysine-arginine balance. The HSV-1 virus needs arginine, another amino acid, to grow and multiply. The theory says that flooding your system with extra lysine could crowd out arginine, slowing down the virus. That idea led many to cut down on high-arginine foods—nuts, chocolate, oats—while boosting lysine-rich choices like dairy, meat, and certain fish.

Side Effects and Risks

Almost anything we swallow for weeks or months can cause issues. Most people tolerate lysine without trouble, but high doses sometimes cause stomach upset or diarrhea. People with kidney or liver problems should talk to a doctor first. The FDA hasn’t regulated lysine supplements as strictly as prescription drugs, so purity and potency depend on the manufacturer.

Taking a Broader Approach

Medication still stands as the backbone for those with frequent or severe outbreaks. Antiviral drugs such as acyclovir or valacyclovir have a strong track record, cutting down both outbreak frequency and symptom length. For a lot of people, mixing tools makes sense—taking medicine, considering supplements, and working on stress and sleep.

If you’re hoping for fewer cold sores, keep expectations steady. Lysine might help—especially as part of a bigger plan. Not everyone notices a change, and skipping medical treatment in the hope of a supplement fix could lead to disappointment. Cold sores carry their own stigma, so open chats with doctors can be a game-changer.

Smart Strategies

Paying attention to triggers matters. If sun exposure sets off an outbreak, sunscreen on the lips does far more than any pill. Managing stress, keeping healthy sleep routines, and eating a balanced diet all stack odds in your favor. If you choose lysine, stick to a reasonable dose, let your doctor know, and monitor for side effects. Read supplement labels carefully and steer clear of grand promises.

Understanding Lysine’s Role

Lysine steps into the spotlight most often as an amino acid supplement for things like cold sore outbreaks or muscle support. It’s not some obscure vitamin; your body needs it, and many diets offer enough. Supplement bottles keep popping up in medicine cabinets because people credit it with everything from fewer cold sores to stronger bones. Lysine isn't a miracle cure, but its popularity comes from a real place—immunity and muscle health matter to people of all ages.

Mixing Lysine With Other Medications

Plenty of people juggle more than one pill daily—antibiotics, blood pressure tablets, cholesterol meds, pain relievers. Most grab a lysine supplement without a second thought. It’s labeled as “natural,” so confidence stays high. Still, lysine does interact with certain medications.

Take calcium supplements, for instance. Lysine’s been said to help increase how much calcium the gut absorbs. That might sound good, but balancing calcium is not something to take lightly, especially for people with kidney problems or older adults already catching too much calcium in their blood.

Some antiviral drugs, valacyclovir to name one, often get paired with lysine for cold sores. Research hasn’t shown clear danger, but there’s a real gap in evidence. Ask a pharmacist, and they’ll tell you—just because problems are rare doesn’t mean they don’t happen.

If someone takes aminoglycoside antibiotics, such as gentamicin (used for tough infections), lysine could be a problem. Both add pressure on the kidneys. Combining them could push kidneys too far, especially if they’re already under strain from diabetes or high blood pressure. Muscle cramping and weakness sometimes develop when amino acids and certain types of water pills are mixed, so keep an eye out for warning signs.

Why This Matters

I’ve watched relatives turn to supplements to "fix" diet gaps after hearing about vitamins on daytime TV. The trust in over-the-counter pills runs deep. There's a belief that if you can buy it at a corner store, risk must be low. That’s not how the human body works; everything that enters your system has an impact. What’s more, older adults or people with chronic illnesses seem most at risk, simply because they stack the most medications.

Solutions That Work

Simple steps make a difference. Keeping a written list of all medicines, prescriptions and supplements—lysine included—can help doctors spot risky combinations. Pharmacists remain unsung heroes; they catch problems before anything turns serious. Spending two minutes to mention every supplement you take at a medical appointment beats hours dealing with a preventable reaction.

Always checking for new research feels tedious, but it pays off. A single new study on lysine interactions might shift advice overnight. If extra calcium, antivirals, or kidney issues are in your story, just ask before adding new pills. Health authorities like the FDA provide alerts online about supplement hazards—keeping an eye on those updates can flag trouble before it hits home.

Personal Responsibility

Trusting your gut doesn’t mean ignoring medical advice. It means being honest about what lands on your plate and in your pillbox. No supplement delivers benefit without risk, even if it comes from a natural source. Lysine can help, but without smart choices and conversations, even a safe amino acid brings surprise twists.