Threonine: A Deep Dive into Its Past, Present, and Future

Historical Development of Threonine

Back in the 1930s, threonine emerged not just as a word in biochemistry textbooks, but as a puzzle piece in the quest to understand life’s building blocks. It’s an essential amino acid, meaning people and animals can’t make it on their own. Scientists hunted for threonine while piecing together how proteins work and how diet impacts health. After William Cumming Rose identified threonine in 1935, it moved from curiosity to necessity. Animal nutrition soon woke up to how much it matters—feed companies began adding it to animal rations hoping for faster growth and healthier livestock. Around that point, researchers realized threonine isn’t just another amino acid; it plays a big role in balancing diets, both for people and industrial-scale livestock.

Product Overview

Threonine shows up today as a pure white crystalline powder, flowing easily and dissolving without a fuss in water. Most of the world’s supply gets produced industrially through a process relying on fermentation, where carefully bred bacteria turn cheap sugars into threonine in big steel vats. This makes threonine reliably available for all sorts of end users. Livestock producers snap it up to boost feed efficiency; pharmaceutical manufacturers reach for it in the lab to develop new drugs; supplement companies look for it to round out their formulations. Cost and purity matter, and modern production lines focus on delivering threonine that’s high-grade, free from contaminants, and consistent in quality.

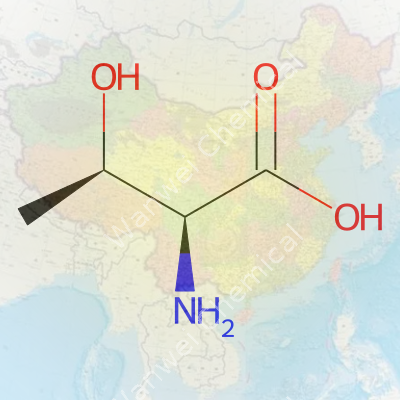

Physical & Chemical Properties

Take a closer look at a pile of threonine and you’ll see a fine powder, colorless and odorless. Touch it, it feels almost soft, not sticky or oily. Drop a spoonful into water, it dissolves without cloudiness—an important feature for both feed mixers and chemists, since solutions need to stay stable for dosing. Chemically, threonine’s formula—C4H9NO3—packs a carboxyl and an amino group along with a distinctive hydroxyl group, which gives threonine more flexibility to react with other molecules. Melting starts just over 250°C, so it doesn’t break down under moderate heat. These characteristics keep it stable enough for global shipping, but reactive enough for use in sophisticated lab processes.

Technical Specifications & Labeling

Manufacturers and distributors label threonine clearly, with content purity (often above 98.5%), moisture limits under 0.5% for stability, and a breakdown of any possible contaminants, whether heavy metals or microbial residues. For human or animal feed, labels must mention the batch number, any allergens, and the country of origin. Standards set by food safety bodies and pharmacopeias—like USP, EP, or Chinese Pharmacopeia—mandate strict traceability in labeling, making it possible to track quality issues back to the source. Pharmacies and veterinarians need that level of detail to guarantee patient safety, and large feed mills rely on specification sheets when formulating feeds to avoid under- or overdosing animals.

Preparation Method

Most threonine leaves the factory thanks to industrial fermentation. Companies start with large tanks filled with glucose or similar sugars, then add strains of Escherichia coli or Corynebacterium glutamicum that are engineered to churn out high yields of threonine. Operators carefully control the pH, temperature, and aeration because even small shifts can drop yields or cause contamination. After several days’ fermentation, technicians filter out the bacterial cells, purify the liquid to isolate threonine, then crystallize and dry the product. The hands-on approach means every batch gets checked for purity, ensuring there’s no carryover from the fermentation process. This method keeps costs down compared to older extraction or chemical synthesis techniques and can scale up to meet worldwide demand quickly.

Chemical Reactions & Modifications

Threonine’s chemical structure pops with reactivity thanks to its two chiral centers and the reactive hydroxyl group. That hydroxyl can participate in phosphorylation, which is key to many cell signaling pathways. In the lab, chemists turn to threonine when synthesizing new drugs, modifying it by protecting or swapping its functional groups to create analogs that might fight disease or mimic natural processes within the body. Enzymes in living systems phosphorylate threonine residues inside proteins, often turning those proteins on or off. These modifications have kept threonine in the spotlight as researchers search for cancer therapies, enzyme inhibitors, and tools to map out hard-to-understand cellular pathways.

Synonyms & Product Names

Threonine goes by a collection of names in various circles. Its IUPAC title reads as (2S,3R)-2-Amino-3-hydroxybutanoic acid, which fits the technical books, but you’ll see it listed as L-threonine on most product datasheets. Sometimes packages use abbreviations like “Thr” or product codes tied to specific suppliers, especially in industrial or pharmaceutical settings. Synonyms include α-amino-β-hydroxybutyric acid and threo-2-amino-3-hydroxybutyric acid. Such names crop up in patents and patent litigation, but everyone in the supply chain links them back to the same fundamental molecule.

Safety & Operational Standards

Factories producing threonine watch carefully for microbial contamination, heavy metal content, and residue from production. Industrial safety teams put systems in place to monitor dust generation during handling since fine powders can trigger respiratory irritation if inhaled regularly. Packaging must keep moisture out and reduce static discharge that sparks fires. Feed mills keep threonine under tight lock and key, training workers to avoid skin contact over long hours and to keep batches away from incompatible chemicals that could cause reactions. Every reputable facility keeps up with OSHA guidelines, and when used in pharmaceuticals or foods, threonine must meet FDA and EFSA standards for purity, documentation, and traceability. Batch records allow for recalls if problems turn up downstream.

Application Areas

Farmers have counted on threonine for decades, using it to stretch protein in animal diets and keep livestock healthy with less environmental waste. By supplementing animal feed with synthetic threonine, producers slash the amount of total protein in diets—this means fewer nitrogen emissions and a lighter impact on soil and water. In the pharmaceutical world, threonine acts as a starting ingredient for synthesizing peptides, vaccines, and even some specialty drugs targeting neurological disorders. Sports nutrition and health supplement makers include it in balanced protein powders aimed at boosting muscle recovery and immune function. Researchers use threonine to study protein folding, cellular signaling, and enzyme action, opening up doors to new therapies.

Research & Development

Biotech companies keep pushing threonine yield higher, tweaking fermentation strains for productivity and byproduct reduction. Today’s genetic engineers regularly fine-tune metabolic pathways to coax more threonine from every liter of feedstock, reducing waste and trimming costs per kilogram. Researchers also test new forms of threonine—chelated with minerals, mixed with slow-release coatings—to improve absorption in animal gut or in specialized diets for people with rare metabolic conditions. In the pharmaceutical labs, scientists continue mapping out how threonine modifications help control key proteins tied to cancer, Alzheimer’s, and infectious disease. Cutting-edge research often zeros in on threonine’s potential as a drug target or delivery vehicle, showing that this simple amino acid is ripe for new discoveries.

Toxicity Research

Extensive studies on threonine’s toxicity paint a generally clean bill of health. Animal trials found that even at doses many times higher than normal dietary intake, side effects stay rare. Overdosing through normal food or feed supplements is nearly impossible; the body handles excess threonine by breaking it down to harmless products. Still, regulatory agencies require chronic exposure studies, especially for genetically modified organisms used in fermentation. These studies focus on tiny risks—impurities, residual bacteria, unknown byproducts—rather than threonine itself, which remains essential for growth in both animals and humans. Safety data sheets emphasize good manufacturing practices more than inherent risk.

Future Prospects

As the market for animal protein and specialty pharmaceuticals keeps growing, threonine’s importance looks set to rise. New sources of protein—like insect or microbial meals—have triggered a fresh focus on amino acid balancing, and threonine holds a central place in that conversation. Research teams keep hunting for next-generation fermentation organisms that make threonine better and faster, reducing sugar needs and environmental impact. In therapies, precision medicine asks for more tightly controlled amino acid inputs; threonine’s unique side chain makes it hot property in that race. Whether it’s in global food security strategies or laboratory breakthroughs, threonine isn’t fading anytime soon, and its journey from rare scientific curiosity to essential industrial commodity offers a model for other bioproducts hitting the mainstream.

Why Threonine Matters

Each time I think about nutrition, I find myself wondering about the stuff most people never talk about—those building blocks that don’t get front-page coverage. Threonine is one of those. It’s an essential amino acid, which means the body can’t make it from scratch. You have to get enough threonine from food, or the system suffers. People don’t go out of their way looking for threonine-rich products at the store, but this little molecule does serious behind-the-scenes work.

What Threonine Does Inside Us

Our bodies burn through amino acids for so many things every day. Threonine’s role covers major ground. It helps build proteins, like others in its family, but goes even further. My grandmother always said, “You need your strength, or your bones and teeth catch up with you.” Threonine backs up her advice. Collagen and elastin—fibers that help skin bounce back, give cartilage its spring, and keep our joints pain-free—rely on threonine. Anyone with a creaky knee or aching shoulders can see the value right away.

The liver uses threonine for fat metabolism. So, every time I see new research about fatty liver disease, I keep thinking how something as small as threonine makes a difference. People who don’t get enough may notice trouble digesting fat or have energy drops before the rest of their diet goes off the rails.

Threonine also fuels the immune system. It’s busy producing antibodies and supporting overall defense against illness. I remember catching the flu one winter, feeling completely wiped out. Back then, I only focused on vitamin C. Threonine, quietly at work, must have been pulling its weight too.

Where to Find It

If someone asks where to get threonine, I usually point to food first. Animal proteins like chicken, milk, eggs, and fish offer strong sources. Vegans and vegetarians can turn to lentils, nuts, seeds, and tofu. But plant-based eaters watch their intake more closely because some plant proteins have smaller amounts.

Deficiency and Supplementation

I’ve spoken with dietitians who see rare cases of threonine deficiency, mostly tied to restricted diets or absorption problems. The symptoms can be rough—fatigue, digestive troubles, slowed growth in kids. Athletes or folks under stress might lean on supplements. People should talk with a healthcare provider before heading to the supplement aisle. The market offers threonine in capsule or powder form, but getting it naturally from food feels right for most people.

Current Research and Potential Uses

Modern science looks at threonine for gut health, especially when it comes to inflammatory conditions. Some studies suggest it supports the lining of the intestines. In hospitals, patients with digestive disorders sometimes receive threonine supplements to help repair tissue. Diabetes researchers find that threonine levels might relate to insulin sensitivity, hinting at future uses beyond standard protein-building.

Personal experience shows me how important overlooked nutrients become, especially as people get older, face more stress, or recover from illness. Threonine gives a solid example of the way everyday nutrition shapes long-term health—and deserves more attention in both conversations and on our plates.

Looking at Threonine in Daily Life

Threonine finds its way into many conversations about nutrition because it counts as one of the essential amino acids. This means the body doesn’t make threonine by itself; it relies on food sources like meat, dairy, eggs, and even some beans. People interested in fitness or who follow a vegetarian diet sometimes look into threonine supplements, wondering how safe it is to use every day.

What is Threonine’s Role?

Threonine plays a real part in how our bodies work. It keeps proteins in the body balanced. It also supports gut health and helps the immune system do its job. Scientists have shown it helps form collagen and elastin, both of which keep skin and connective tissues strong. Without enough threonine, muscles may not recover well, and digestion can get off track.

How the Body Handles Threonine

Getting threonine from food usually causes no trouble. The body regulates how much it uses and gets rid of the rest. The trouble often begins when people turn to strong doses of supplements without paying attention to daily needs or existing health problems.

Daily Use Safety and What the Science Says

Research hasn’t flagged threonine as a danger for healthy adults when sticking to suggested amounts, which usually sits around 500 mg to 1,000 mg per day from all sources. Scientists found healthy kidneys filter out extra amino acids, including threonine, when levels get too high.

Problems tend to show up only with heavy supplementation over time. Some studies point to risks like nausea, headaches, or upset stomachs if doses creep up far past normal diet levels. Medical research in humans doesn’t show any links between normal dietary threonine and organ damage. Still, no supplement beats what you get from a healthy plate of food.

Concerns People Often Miss

People with liver or kidney conditions sometimes get told to watch their protein or amino acid intake. Too much threonine, just like too much protein, might make these organs work harder than usual. Anyone in these situations should check with a doctor before adding supplements.

Young children, women who are pregnant, or people with rare metabolic issues also need extra care. The standard safety data often focuses on healthy adults, so talking to a healthcare provider before starting new supplements makes sense.

Building Safer Habits

Doctors and dietitians almost always suggest getting threonine from food. Chicken, cottage cheese, spinach, and nuts cover most people’s needs. The supplement aisle may seem appealing, but pills never replace the benefits of a balanced plate. If someone still wants to try a supplement, looking for products from companies with strong reputations helps cut down on risks tied to untested additives.

Key Takeaway

It’s smart to stay mindful about what goes into the body every day. Threonine, in the amounts found in regular food or basic supplements, stays safe for most healthy adults. Paying attention to overall protein intake, focusing on real food first, and keeping in touch with a healthcare provider covers most of the safety ground.

Threonine’s Role in Daily Health

Threonine stands among the essential amino acids, meaning the body requires it but doesn’t make it on its own. People get threonine from foods or supplements. This amino acid helps with protein growth, keeps the immune system on track, and supports the liver. Without enough threonine, muscles can break down, or a weakened immune response can lead to more frequent illnesses.

Best Sources and Recommended Amounts

Healthy adults usually hit their threonine targets just by eating a balanced diet. Animal proteins such as chicken, beef, pork, and fish pack in plenty of threonine. Dairy and eggs do too. Even vegetarians, if they focus on beans, lentils, nuts, and soy, can pull in enough.

Based on information from the Food and Nutrition Board at the Institute of Medicine, adults need about 20 mg per kilogram of body weight per day. For a person weighing 70 kg, that’s about 1.4 grams each day. Athletes or people healing from injuries might look to protein powders or amino acid supplements, but most folks get by just fine with a regular diet.

Why Dosage Matters

Protein supplements flood the health market. Many aim to boost muscle growth or replace lost nutrients. Some people assume more means better. In reality, the body can only use a set amount of threonine at a time. Extra gets burned as energy or passes out of the body. Consistent overeating of one amino acid can start to mess up how the liver works, tilt nutrient balance, or stress the kidneys.

In my own life, juggling gym routines, busy workdays, and family meals, I’ve run into lots of hype around amino acid pills. Friends ask if upping threonine intake gives a real energy boost or sharper focus. After looking closer at the research, the science doesn’t back up massive doses unless someone has a clear medical reason, like a doctor-diagnosed deficiency or rare genetic disorder.

Risks of Too Little or Too Much

Too little threonine can creep up in people with eating disorders, certain restrictive diets, or chronic illnesses affecting absorption. They might notice sluggish energy or weakened muscles. At the other end, high-dose supplements bring their own risks. Side effects range from stomach problems to headaches and trouble sleeping. Long-term, kidney issues could show up if aminos are way out of balance.

Using Supplements Sensibly

Supplements make sense for some — older adults losing muscle, athletes in heavy training, or people recovering from surgery. No pill fixes a poor diet, though. For most people, focusing on whole foods gives the body what it needs. If a supplement seems necessary, checking with a physician or registered dietitian makes a big difference. They consider everything from current health to medications and design a plan that really fits the person.

Looking Toward Better Health Choices

Eating habits shape how the body uses nutrients such as threonine. Trusting the foundation — meals built around real, unprocessed foods — gives lasting benefits. Periodically, checking in with a qualified healthcare provider ensures nothing gets missed. Marketing buzz fades but smart, science-backed choices stick around.

Why Threonine Gets Noticed

Walk into any fitness store, browse a health forum, or scan nutrition labels, and threonine pops up. This amino acid helps the body build muscle, keeps your digestive tract comfortable, and plays a role in immune health. Plenty of people eat enough protein from meat, dairy, or legumes, so most folks don’t need to worry about getting enough. Still, many athletes, bodybuilders, and people chasing recovery after injury consider bumping up threonine with supplements.

Pushing for More: Does Extra Threonine Do Harm?

More isn’t always better. Doctors and nutritionists warn about loading up on any amino acid, including threonine. Most studies show that moderate doses—often under 2,000 mg daily—rarely cause trouble in healthy adults. Step above the usual range, or go wild with powder and capsules, and the body starts getting overwhelmed. Some people have reported stomach discomfort, diarrhea, and headaches after large doses, especially on an empty stomach. Others mention sleep changes, feeling jittery, or a sense of restlessness—issues that hint at threonine’s effect on the nerves and brain chemicals.

People with certain medical conditions, like kidney or liver disease, face bigger risks. Their bodies can't safely clear excess amino acids, so too much threonine might do harm. For anyone on prescription drugs or with existing metabolic concerns, mixing supplements adds another layer of risk. The science still lags behind real-world use. Researchers haven’t run many long-term safety studies, so nobody can say for sure how daily high-dose use pans out over years.

What Real Experience and the Science Say

Nutrition isn’t one-size-fits-all. I’ve worked with folks who swore threonine “took the edge off” sore muscles or sped up their healing after surgery. Some did great for months—until gut problems or trouble sleeping made them rethink their supplement stack. Tuning in to the body’s response matters. A sudden burst of digestive trouble or nervous energy deserves attention, not a “push through it” mindset.

Labs and nutrition experts usually advise starting low and tracking how you feel. No supplement solves every problem, and eating a balanced diet with lean proteins covers most threonine needs. Medical sources highlight that the body self-regulates amino acids from natural food, but supplemental forms can tilt that balance.

Safe Use and Smarter Solutions

Most health pros agree on a few commonsense rules. Check labels for hidden ingredients or mega-doses. Listen to your gut—literally and figuratively. If unexplained symptoms pop up, start by scaling back. If you’re thinking about stacking threonine on top of other amino acids, ask a registered dietitian or doctor. The Food and Nutrition Board points out that nobody’s determined an official maximum for daily threonine intake—another sign that caution pays off.

For folks hoping to recover faster or improve performance, building a solid plan matters more than leaning on any single powder. Aiming for protein from whole foods, keeping hydrated, and getting sleep works better than chasing the latest amino headline. For people with health conditions or those on medication, any new supplement deserves a careful look and a real talk with a health provider. The user experience matters as much as the science, and good health means both listening to the research and trusting your own body’s feedback.

Amino Acid Basics and Why People Use Threonine

Amino acids may sound complicated, but for most people, they're just part of daily nutrition. Threonine belongs to the set of essential amino acids—nutrients that the body can’t make, so food is the way to get them. Supplement companies sell threonine for muscle recovery, liver health, and sometimes for better gut function. Plenty of health aficionados put it in their shakes, especially those who track every nutrient after a workout.

Mixing Threonine With Other Supplements

People mix threonine with other amino acids—think lysine or methionine—for muscle support. In the gym world, protein powders already combine these building blocks. Food delivers them in balance, but supplements sometimes tip the scales. Most healthy adults who eat a well-rounded diet get enough threonine, but athletes or vegans sometimes want more and try to fine-tune intake by stacking it.

B vitamins, magnesium, and zinc often show up in routines alongside amino acids. No published studies flag any serious problems from pairing those minerals or vitamins with threonine. Still, it pays to read the ingredient lists—some combos push nutrient levels much higher than what’s safe, especially if multiple supplements overlap.

Threonine With Medications

Doctors don’t usually get too concerned when people ask about adding threonine to a diet—unless prescriptions enter the mix. Threonine itself doesn’t have a stack of clinical warnings attached. But any amino acid supplement has the potential to tinker with how the body processes certain drugs.

For example, people taking medications for liver disease or seizures face unique risks. The liver breaks down most drugs and nutrients, so extra threonine can sometimes add more pressure. Those with chronic kidney problems walk a fine line—too much protein, whether in food or through isolated supplements, turns into extra work for kidneys. Pharmacists I’ve spoken with often say patients skip mentioning over-the-counter amino acid supplements unless pressed about their “health store” routine, so doctors might not know when a problem crops up.

Some anti-epileptic drugs influence amino acid metabolism, meaning a sudden bump in intake could affect blood levels or side effects. No strong clinical trial data links threonine itself to dangerous drug interactions, but researchers just haven’t studied this much. What’s safe for an active 25-year-old isn’t automatically fine for someone managing liver disease, depression, or high blood pressure.

Ways to Use Threonine Responsibly

Checking with a physician or pharmacist before adding threonine—especially on top of prescription meds—brings peace of mind. Health professionals can help review ingredient labels and spot red flags in drug interaction databases. For those who already take a balanced multivitamin and eat well, separate amino acid supplements don’t always add much, but targeted use for strict vegetarians or heavy trainers isn’t rare.

Fact remains, the supplement industry in many countries leaves most of the research and regulation up to consumers. Not all products get tested for integrity or contamination. Checking third-party certifications and avoiding sketchy brands adds some reassurance. If new symptoms show up after starting a supplement—like digestive upset, headaches, or changes in blood pressure—stopping use and checking in with a healthcare provider makes good sense.

Threonine can play a role in nutrition, but balancing it with both diet and health conditions means looking at the whole picture, not just one bottle in the cabinet.